When Bob’s Design Engineering in Hillsboro, Oregon, won a major production job three years ago, the shop’s owner and senior employees had just one question:

“Now what?” they asked.

They had not expected to win this project. As the very name of the company suggests, Bob’s Design Engineering has historically been focused on prototyping and short-run product development, not machining for mature production. In fact, many of the company’s customers are in the electronics industry, which has a long history of sending production overseas. So when a maker of commercial printing machines asked Bob’s to quote on the full production of about 125 part numbers (later increased to 250), owner Bob Hale initially balked. He assumed that a quote from a U.S. source would simply be used to benchmark Asian suppliers.

The reality was different. As it happened, this customer was ready to seek an American supplier. Bob’s, which had delivered prototype parts for these printers, was a logical choice. As effective as the shop had been at prototyping, could it be just as effective at developing processes for recurring production? Apparently, yes, as the shop’s quote kept advancing through round after round of bidding. Ultimately, the shop learned that its pricing was not just lower than other American suppliers, but also even lower than the cost of overseas production—a surprising development resulting from two important factors in particular.

One was shipping and travel cost. While Bob’s is close to the customer, Asian suppliers are on the other side of an ocean. From experience, the printer maker had learned how to make a fair accounting of the true cost of this distance, including the expenses associated with sending U.S. engineering support personnel to Asia and carrying extra inventory as a buffer against lengthy shipping times. Factoring in all of the extra expense significantly reduced the seeming cost advantage of overseas production.

The other factor was Bob’s Design Engineering’s level of machining expertise. Like many small shops, Bob’s has a staff that includes a small core of veterans with decades of experience. Members of the senior staff here average 25 years in manufacturing. Traditionally, the shop has applied this experience to making short runs of parts that might never be seen again. To bid for this job, the shop directed this same expertise toward imagining cost-effective processes for parts that would be machined repeatedly.

Tool Engineer Jim O’Leary was one of the senior staff members who took on process development for the production work. Soon after winning the contract, the shop moved to a larger facility and increased its number of CNC machines—largely in answer to the new demand. Yet even with these changes, the shop could not afford to fully and immediately reinvent itself by shifting all of its new work to production-oriented machines such as horizontal machining centers. Instead, Mr. O’Leary’s mission included making the shop’s existing vertical machining centers effective for production of recurring parts.

Part of the way he did this was by minimizing cycle time. Experimenting with new cutting tool designs and toolpath choices in search of cycle time savings is still an important part of his job.

But at the beginning, the much greater opportunities for efficiency improvement were found outside the cut. To allow the shop to become as cost effective as possible in full production, Mr. O’Leary and others at Bob’s gave careful attention to process elements including workflow within the machining cycle, setup design and the efficient management of the shop’s broad range of tools.

Almost Like a Horizontal

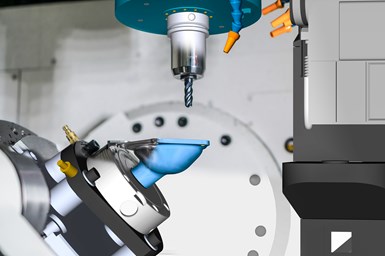

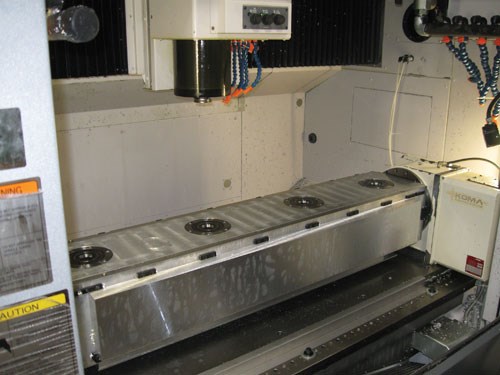

The setup in the third photo at left, which is typical of the way the shop now runs production, shows what is meant by workflow within the machining cycle. “Done in one” is the objective, Mr. O’Leary says—meaning a finished part should be produced in every cycle. While the shop now has HMCs for full-scale production (more on that later), this process on a VMC enables this machine to achieve levels of feature-to-feature consistency that are close to a horizontal’s performance.

The part shown in those photos gets machined on all six faces. Three stations within the machining envelope are needed to achieve this, the third of which is a fourth-axis indexer. Effectively, there are four stations, because a quick-change fixture plate for the indexer is set up outside the machine while the machining cycle runs. At the end of every cycle, the operator pulls this fixture plate off the indexer and pulls a completed piece off of the plate. Workflow then proceeds as follows: The operator places a fixture plate that is ready to go with a vise-B-machined part into the indexer. The operator then pulls the workpiece from vise B, flips the workpiece from vise A into vise B and loads a fresh workpiece into vise A. Then, taking advantage of the time while the machining cycle runs, the operator clamps the original part from vise B onto the fixture plate outside of the machine. All of the stations are thus needed to complete any piece. Change-over between machining cycles requires about 2 minutes, and every machining cycle from the fourth one forward produces a completed part.

Setups such as this one are engineered not only for efficient machining, but also for rapid machine change-over, Mr. O’Leary says. With the arrival of the recurring work, Bob’s equipped its VMC tables with subplates from

Stevens Engineering. Workholding elements are mapped to clamping holes in these subplates so that recurring setups can be torn down and built back up again quickly.

On rotary axes, where precise location is particularly important because of the trigonometric effect of the rotation, the shop uses the Unilock self-locking clamping system from

Big Kaiser to hold the fixture plate that holds the part. Within the three-station setup, for example, a Unilock receiver has been precisely positioned at the rotational center of the indexer. This assures rigid clamping that is simultaneously accurate and fast. For a long part positioned along a different indexing fixture, Unilock receivers are aligned along the fixture’s centerline (see photos).

Add-On Tool Management

Mr. O’Leary says the shop’s management of its cutting tools also had to be rethought—a step the shop was overdue to carry out. Cutting tools formerly were scattered throughout the shop, often found in the tool chests of employees who expected to use that tool again. The seeming convenience of allowing employees to hold tools this way was anything but convenient, because it left employees searching for the tools they needed. To save time, Bob’s knew it needed organized and centralized tool control.

The system the shop chose was developed by its tooling distributor, Western Tool & Supply. Western’s invention, called the “Future Tool System” (FTS), adapts existing tool cabinets to create a controlled-access tool management approach that is comparable to tool vending machines.

The FTS system uses computer-controlled locks installed on the tool storage cabinets in the shop’s newly outfitted tool crib. A PC running a simple FTS software interface controls the locks. For Bob’s, the result is a streamlined system in which employees no longer search for particular tools, but instead select them within this utility. The software identifies the correct drawer for the tool and unlocks the appropriate cabinet. The system also automatically adds the requested tool to the list of withdrawn inventory that will need to be restocked later. Whether the tool type is commonplace or obscure, any employee can now obtain a needed tool in seconds.

While production provided the reason for installing this system, Mr. O’Leary says the shop could have used it all along. Eliminating the time spent searching for little-used tools would have made prototyping more efficient as well.

Moving Forward

Not every outcome of the shop’s shift toward production has been positive. A few years after the surprise of winning the printer-related work came the negative surprise of seeing the work slack off. Demand for the printers currently is not on pace with the expectations of the shop’s customer, so orders for components have declined. Lately, in fact, the shop has gone through a period of machining no printer-related parts—filling demand out of inventory instead. Having expected a higher level of demand than this, the shop recently installed a new

Okuma pallet cell with two HMCs. As it turned out, the new capacity could be brought online slowly, because there was no longer any urgency about bringing it into use right away.

The lull changes nothing in the long term, Mr. O’Leary says. The transition into production was still the right move for multiple reasons. For one, other customers and prospects in the shop’s sphere are also contemplating either new or reshored production in the United States. Opportunities are increasing. The previous illustration of the three-station setup, for example, showed a production part unrelated to the printer customer.

Another reason why the production work is valuable relates to future staffing. The machining expertise that let the shop develop and implement its production disciplines will leave the company as senior staff members reach retirement age. Young employees with relevant skills are difficult to find, Mr. O’Leary says, so they often have to be trained in basic skills on the job. As a result, he believes the right model for the shop’s future success will be not just production, but systemized production of the sort that the shop’s staff has been working to put in place. Along with creating production methodologies, the shop also has been creating a framework of well-defined procedures that will enable new employees to start delivering value even when they enter the organization with a low level of manufacturing experience. Prototyping work could not have provided this context.

The company name will even change, he says. “Bob’s Design Engineering” is no longer descriptive of the type and range of machining work in which the company’s future is likely to be found. The new name—a more inclusive one, encompassing the company’s more diverse range of services—will be BDE Manufacturing Technologies.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Fast CNC processing and high-pressure coolant contribute to removing metal at dramatic rates. But what should a shop know about cutting tools in high speed machining?

-

Running rotary milling cutters at the proper speeds and feeds is critical to obtaining long tool life and superior results, and a good place to start is with the manufacturer's recommendations. These formulas and tips provide useful guidelines.

-

The more common twist drill point geometries often are not the best for the job at hand. By choosing the best point for the material being drilled, it is possible to achieve better tool life, hole geometry, precision, and productivity.

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)

(1).1676494398075.png)