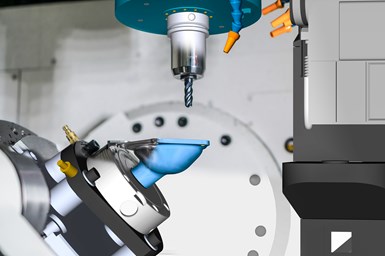

The fight to reduce runout and control heat generation is familiar to every machinist, but it does not affect every process equally

Managing Heat for Microdrills

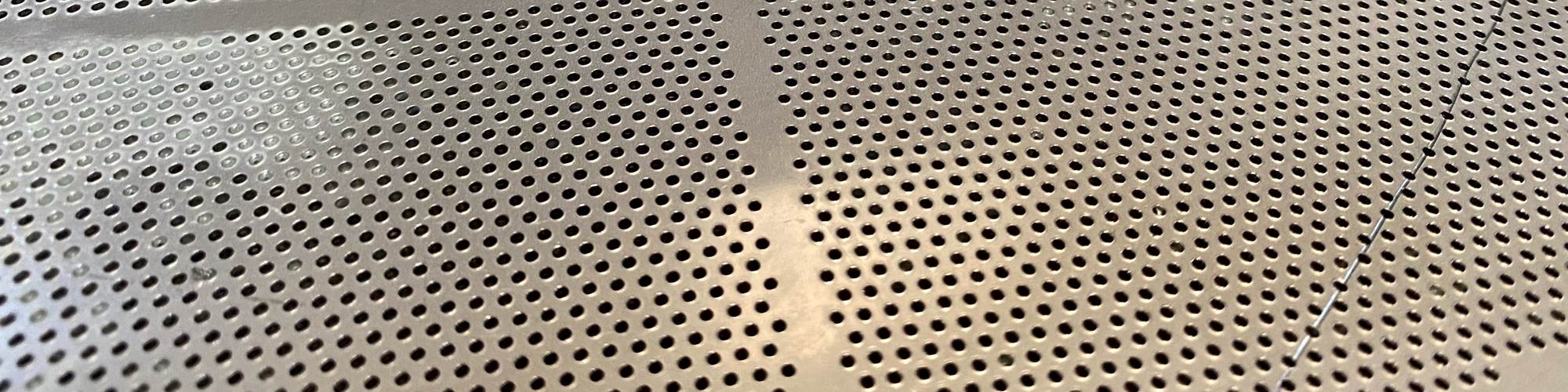

The application involved making a screen from large, flat stock of 316 stainless steel. The part needed thousands of holes drilled at 1-millimeter in diameter, which combined the challenges of microdrilling with heavy wear on the cutting tool.

Featured Content

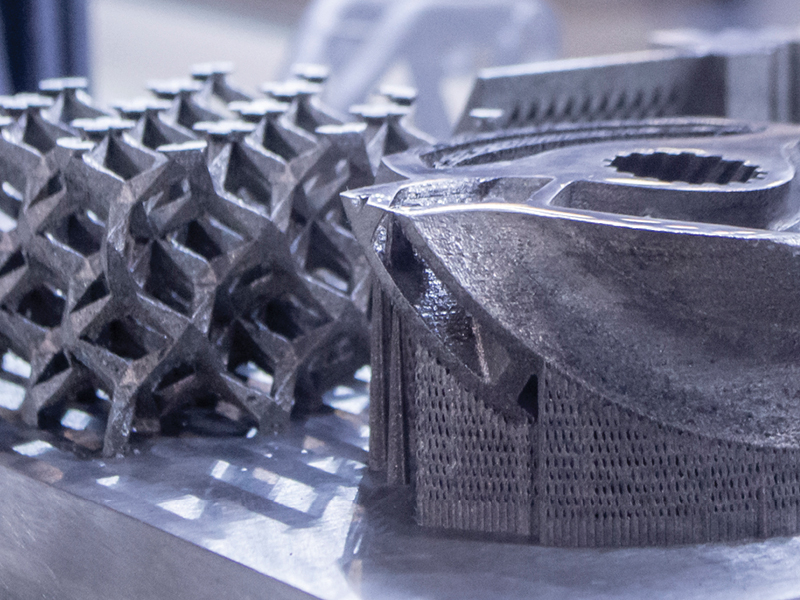

Aspro Plastics manufactures parts for the plastics industry, including this stainless steel screen. Producing this screen involves drilling 44,816 holes at a diameter of 1 millimeter. Photos courtesy of Sandvik Coromant.

The heat generated by the drilling process, as well as the large number of holes needed, quickly wore out drills. This necessitated multiple tool changes for each part, increasing the time spent on the machine tool. Additionally, the drill’s size made managing heat more difficult, as the machine could not supply through coolant, making external coolant the only option. This made things more challenging, as controlling heat generation was vital to prevent work hardening, Lind says. At only 1 millimeter in diameter, drills easily snap under the additional strain of hardened material.

Aspro turned to the Coromant 1-mm 9×D X2BL microdrill, which nearly halved the machining time per hole and reduced the number of tool changes per part.

Working with Sandvik, the shop opted to revise its process. It eventually settled on using a Coromant 862 family drill, the 1-mm diameter 9×D X2BL microdrill. While this drill was a major improvement,

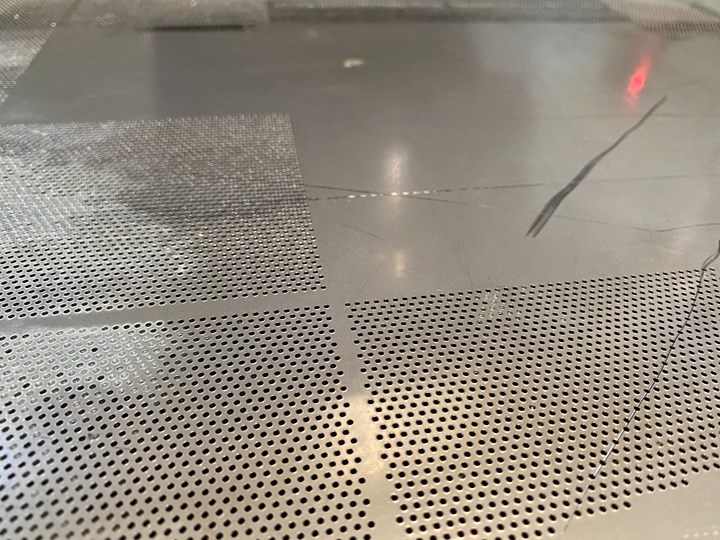

Pecking at the Part

Particularly at the micro level, the right tooling and machine tools are not always enough to succeed. Overcoming the challenges of this application meant pecking: repeatedly pulling the tool back during the drilling cycle to remove chips and dissipate heat.

By “pecking,” Lind says he means engaging the material at an initial depth of approximately 1-3×D and then subsequent “peck” depths of 0.5-1×D until the desired depth is reached. The drill must not leave the hole completely, as fully exiting and reentering the hole risks damaging the tool. Instead, it withdraws just enough for the flood coolant to evacuate chips before reengaging the part. All of this is performed on a Haas VM3.

“There’s not much room for forgiveness when working at this size,” he says. “You will break your drill if you’re not careful.”

In cases where pilot drilling is necessary, it’s important to limit the spindle to 500 RPM at no more than 50% of the programmed feed rate so the tool can locate itself. Once the drill is engaged and 1-2×D into the part, increase to the recommended cutting data. Also, in cases where coolant-through tools are used, it’s imperative to leave the coolant off until the tool is engaged and stabilized in the pilot hole at least 1-2×D deep prior to turning on high-pressure coolant.

To manage heat and evacuate chips, Aspro used a “pecking” toolpath in which the drill repeatedly pulls back during drilling to remove chips.

Even without fully exiting the hole, constantly breaking off contact and reengaging the drill causes a great deal of wear, as it constantly shifts the forces acting on the cutting tool. “Usually, constantly disengaging and reengaging the part is something to be avoided,” Lind explains. “But in this case, it’s the lesser of two evils compared to breaking the drill.”

Increased Productivity

The new drill and revised process led to a 300% productivity increase. “With the old drills, the machining time was eight seconds per hole,” Lind says. “We got that down to 4.7 seconds.” Additionally, the X2BL microdrill is capable of handling many more holes before a tool change while producing a surface finish exceeding 32 RA. “The facility went from handling 6,800 holes per drill to 10,000,” Lind says. “So they’ve reduced the tool changes to four in-process changes per part.

“The Sandvik Coromant microdrill was just the fit for us, because we reduced our cycle time by more than half, with improved cut parameters,” Ferreira concludes. “We also had the confidence that the drill could work overnight, saving us working machine hours. As a result, we saved about 40 hours per component.”

RELATED CONTENT

-

Tool Considerations for High Speed Cutting

Fast CNC processing and high-pressure coolant contribute to removing metal at dramatic rates. But what should a shop know about cutting tools in high speed machining?

-

Machining Dry Is Worth A Try

Reducing cutting fluid use offers the chance for considerable cost savings. Tool life may even improve.

-

Choosing The Best Drill Point Geometry

The more common twist drill point geometries often are not the best for the job at hand. By choosing the best point for the material being drilled, it is possible to achieve better tool life, hole geometry, precision, and productivity.

(1).1676494398075.png)